I open a door an emerge into a garden. I’m speaking a different language, something that I identify as Spanish but sounds nothing like it. I have arrived somewhere I need to be. Just ahead, two women walk, talking to each other in the same language. I am aware that they are people I have been wanting to meet. I follow them.

This is the synopsis of a dream I had just before waking sometime this week. I don’t know why, but it felt like the correct preamble for what is to follow.

What follows is a journal I never kept but lives inside my head nonetheless, a journal whose timelines spill over each other and entwine the farther and more recent past. I thought I’d give this journal form after reading Dimitri Nabokov’s essay “Close Calls and Fulfilled Dreams” - a similar exercise in autobiographical writing that does these acrobatics with time, which was part of the Alex Chee craft seminar.

What results is a story - the story of a story - that I knew to be mine but never knew to be so fascinating.

As you read, be gentle with yourself and don’t spend too much time trying to decipher exactly what happened when. In the end, it doesn't really matter.

7th June, 2006, Bandra, Mumbai

It’s 6am, and I’m looking for inspiration. I make a list of things I feel I ‘know’. It’s dark, and the room feels charged with promise. I write:

Old People.

Acne.

The list continues. Eventually I start writing about my grandfather who had trouble remembering things in his last decade of life. He’d channel his irritation at forgetting onto others, usually for forgetting the date of the French revolution’s commencement. He’d test them. If they didn’t know, he’d playfully hit their knuckles with a wooden ruler. I remember his eyes. Behind the playfulness, there was helplessness and vulnerability.

In the days that follow I would write a story about an old photographer who forgets his life and then is assisted by his wife in remembering it. In the years that follow, I would turn that story into a tight screenplay born more of intuition than skill. A month after writing the screenplay, I would resign from my job as an assistant director and ask my father permission to take a sabbatical from work and try to become an independent filmmaker. It would be a decision that would allow me into a frame of mind where I would say yes to marriage, say yes to taking on an agent and say yes to a producer who’d want to turn the screenplay into a film. In the years that follow, my wife, my agent and my producer would become my closest friends and together - directly and indirectly - we would all be on a journey where my story of the old photographer (and perhaps the choice to leave the subject of skin affliction behind on that Bandra morning) would be as much a participant in my life as any of the people I considered important.

4th September, 2006, Alibaug

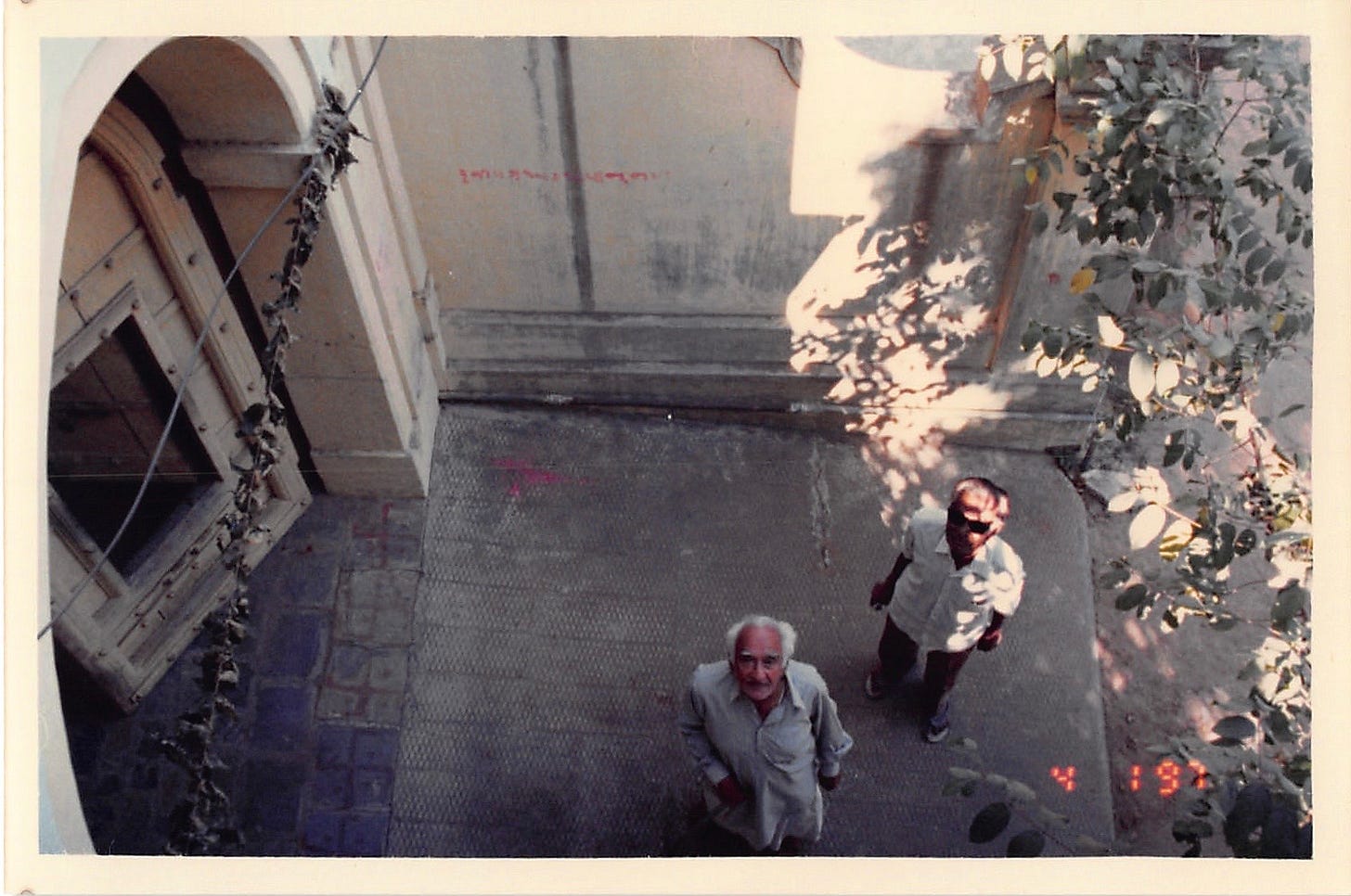

I sit with Dashrath Patel, the father of India’s coveted National Institute of Design, and talk to him about the story I want to write about the photographer. My current boss sends me to him after I pitch him the idea about the photographer who forgets.

After showing me some photographs he took while travelling in Japan with Henri Cartier Bresson, Dashrath Bhai ‘gifts’ me one of his experiences as a photographer - one where he almost got killed in the jungle by angry tribesmen in an era when the county’s indigenous tribes were freshly peeved by the governemnt’s and civilisation’s unwelcome encroachments. His gift would become the opening scene of my story - this story I am yet to write in earnest, the story that will change my life and catapult me towards becoming a filmmaker. But there are still some years before any of this will happen.

Fifteen years later, I would return to this same house in Alibaug, this time with my wife and children. Dashrath bhai would have been dead for some years, but his longtime business partner would be around. I’d ask to meet him but I’d be told he’s busy. I’d leave him a note asking to meet later and tell him about how that meeting with Dashrath bhai was so significant for me - about how it led to the writing of a story that suggested that maybe, I was writer. I’d never hear back from his partner, but I’d enjoy seeing Dashrath patel’s paintings and personal artefacts on display. He had a thing with shapes and textures. A real eye for colour and symmetry.

Three years later I would quit my job after a film that I helped develop for the past five years ceased production a few weeks before principal photography. I would break down and cry before my ex-boss, feeling as if my arm had been cut off. A few months later I’d be writing the story about the photographer as a means to grow that arm back. My ex boss and I would - over the years grow into friends, finding a deep and trusting friendship born of crashing hard together. He’d dance spectacularly at my wedding.

1st August, 2009, Calicut, Kerala

I am staying at the Malabar Palace hotel, having a daily conversation with MT Vasudevan Nair about my story. He’s graciously agreed to keep some time for me every day. After we finish our morning conversation, we have lunch. After lunch, MT lies down on the bed covering himself with a towel and presses his two index fingers into his cheeks. This is how he sleeps. After 30 minutes he’s up and we talk some more.

After hearing about my ambition to tell a story about a photographer, he encourages me to read The Bridges of Madison County, which I savour from beginning to end. I’m struck by how erotic the book is, and in the coming weeks, I’ll be experiencing for the first time, what it means to write sensually. I will also have Clint Eastwood pervade any senior male character I write. It will be years before Eastwood is replaced by others, notably by Ben Kingsley.

Many years later, my producer and friend Michael and I will be standing outside the London offices of Ben Kigsley’s management agency, waiting to meet his agent and pitch our film about the ageing photographer who forgets to him via her. A hours later, we’d be sitting in a pub wondering why we had been dismissed so unceremoniously. London was very cold at the time.

10th August, 2009, Bandra, Mumbai

For the first time in years, I do not have to report to an office for work. I’m writing incessantly. In between writing I’m watching video podcasts about Magnum photographers doing their thing. I’m filling up empty RTF documents with large swathes of text. I usually begin with a question and then try and answer it. I’m surprised by how much I have to say in answer to my questions about my story and its world. My story. This is the first time I feel a sense of propriety over something as, till now, nebulous as a story. It’s heady, this feeling. At nights I meet friends at Zenzi, Bandra and while present before them, there seems to be a new part of me that none of them can see - a self living inside the new world I’m slowly creating. It feels like a well kept secret.

A year later, everything I had written about my photographer feels like crap. I negate it, cross it out, rewrite and the result is even crappier - drafts and drafts I’d never read again. Fifteen years later, I’d read my first notes again and know that these are likely the purest things I have ever written, loaded with a power I would take me ten years to learn how to replicate.

10th August, Locarno, Switzerland

A tall blonde man comes to my desk at the co-production workshop I’m attending and tells me that he has not been able to get the story of my photographer out of his head since he read it. In the evenings, Vani and I attend cocktails at castles and watch esoteric arthouse films. The films bore her. Some of them amuse me.

A few months later, this blonde man - Michael - options the screenplay. A few years later, he and I drink Guinness at a pub in London genuinely flabbergasted that Sir Ben Kingsley’s agent turned us down. A year before this Guiness in London, Michael calls me in Mumbai and asks me to sit down before telling me that our script had become the first ever Indian project to be granted development funding by the European Union. Seven years after our meeting in Locarno, Michael cannot make it to India on time for the prep of a shorter version of our film because his dog knocks him over during his Easter vacation and he fractures his elbow in a spectacularly grotesque way.

24th June, 2013, Mandawa, Rajasthan

I am in Rajasthan, following the trail that my imagination sent my photographer on. I see the drying wells that are part of the story when it takes its most unexpected turn. I shoot hundteds of photos of desert trails, seeing one motif after another that I dream of putting inside my film as if it was a Christmas tree. I drive the very car that I chose for carrying my photographer on his journey; feeling the fatigue in my arms after working its hard steering wheel for an hour. I rewrite a dialogue in the screenplay “driving this thing is hard on the arms”. Life feels so good. I do not feel the 41 degree Rajasthan heat.

I want to go to Diu but cannot on this trip. Eighteen years ago, I had crossed over from Rajasthan into Gujarat and finally into Diu with my parents in a hard-top Maruti Gypsy. It felt as if I had come to another country - the churches and the Portuguese forts and the people. Bullock carts with expended airplane tyres. The landscape of my story’s finale. A year after this Rajasthan trip, my children are born. As they grow - every road journey I take with them is held up against that trip to Diu with my parents to check for comparisons. I use that trip as a benchmark for whether all later trips with my children amount to formative experiences or not.

21st November, 2015, Panjim Marriott, Goa

I sit in Michael’s room at Film Bazaar looking out at the sea from the Marriott Hotel. I have never felt worse about my prospects as filmmaker in my life. Almost every door we have knocked on to bring our story to life has refused to open. In my mind, the world’s patience for my whims is running out. It seems to be asking me - ‘When will you wake up and see things for what they are?’ I am frightened of the answer to that question.

Eight months later, I meet an executive from Netflix at the Mumbai Marriott hotel. They want me to be a writer on their first original out of India. They have read my photographer story and tell me that they love it.

Two years later, I am in New York attending the International Emmys, where the same Netflix series has been nominated in the best drama category. My partnership with Michael is stronger than ever. He and I know we will make our film. For now we let it rest, and decide to revisit once we’re both stronger and wiser.

3rd August, 2022, Andheri, Mumbai

I pull up my last draft of the photographer story and read it. It’s been five years since I read it last. As I read, the hair follicles on my arm stand upright again and again, involuntarily. I wonder - with all humility - how did a story like this ever emerge from me? I never quite came around to believing this, and - with all humility - I still find it difficult to fathom fully. But it feels like a gift, despite not having yet reached its logical culmination of being made into a film. After awhile, you need to shut up and take the gift, and not ask too many questions.

I text Michael about how I feel after reading. We both agree - this film must be made. We both reaffirm our determination to make it. We’ve never stopped running with it, that much is clear. We have no plans on stopping either.

Later that day, I see an Uber on the road with a strangely banal message stuck to its rear windshield. It feels like it’s meant only for me:

…to be continued.

Thank you for reading Yet Untitled. My hope is that this edition resonates. If it does, tell me - in what way? I want to know!

Also,

Lots of love,

V

It sounds like a spectacular screenplay. May I read it? Also, I love how when we cross paths with certain words at a certain time—no matter how banal—they appear so personal, so profound. As an aside, a (female) photographer is one of the main protagonists in my latest book.

Thanks so much Prateek. Will share soon. Hope you are well!